BCG InstituteBCGi

Content Validity

There are three (3) primary forms of validation presented in the Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures (UGESP): content, criterion-related, and construct-related (in the order most frequently used by employers).

Content validity. Demonstrated by data showing that the content of a selection procedure is representative of important aspects of performance on the job. See sections 5B and 14C of the UGESP.

Steps for Completing a Content Validation Study

There are four steps for conducting a conventional content validation study: job analysis, selection plan, selection procedure development, and selection procedure validation. The first two steps form the essential foundation of a professionally-conducted content validation study, and are the same regardless of the type of selection procedure that will be validated (e.g., a written test, physical ability test, interview, etc.). The steps and requirements for completing the last two steps are highly contingent on the type of selection procedure used.

A job analysis consists of a thorough analysis of the job duties and knowledges, skills, abilities, and personal characteristics (KSAPCs) required for a position. A selection plan extracts from the job analysis the key, essential KSAPCs and/or job duties that should be measured by the selection process. The steps for completing each are provided below in BCGi Resources, and the following section(s) describe how to develop and validate content valid selection procedures that can be linked back to the job analysis and selection plan components.

Eight Steps for Completing a Job Analysis

Developing a thorough and accurate job analysis is the most important step in a content validation study (it is also important for criterion-related validity, but less so). It is analogous to framing and pouring the foundation of a house—without a strong foundation, the rest of the building does not matter. The rest of the house will be either upright and stable, or crooked and shaky.

There are numerous ways to complete a solid job analysis. While there is no “one right way,” the steps below are provided as a template for developing a job analysis designed to provide a foundation for validation. This process is adopted from the Guidelines Oriented Job Analysis® (GOJA®) Process, which has been supported in numerous EEO cases* and reviewed in several textbooks and articles.** An evaluation copy of the full GOJA Manual is included on the Evaluation CD.

* Some of these cases include: Forsberg v. Pacific Northwest Bell Telephone (840 F2d 1409, CA-9 1988; Gilbert v. East Bay Municipal Utility District (DC CA, 19 EPD 9061, 1979); Martinez v. City of Salinas (DC CA, No. C-78-2608 SW (S.J.); Parks v. City of Long Beach (DC CA, No. 84-1611 DWW [Px]); Sanchez v. City of Santa Ana (DC CA, No. CV-79-1818 KN); Simmons v. City of Kansas City (DC KS, No. 88-2603-0); and US v. City of Torrance (DC CA, No. 93-4142-MRP [RMCx]).

** Buford, J. A. (1991), Personnel Management and Human Resources in Local Government. Center for Governmental Services, Auburn University. Gatewood, R. S. & Feild, H. S. (1986), Human Resource Selection. Drydan Press; Buford, J. A. (1985), Recruiting and Selection: Concepts and Techniques for Local Government. Alabama Cooperative Extension Service, Auburn University; Schuler, R. S. (1981), Personnel and Human Resource Management. West Publishing Company; Bemis, S. E., Belenky, A. H., & Soder, D. A. (1984), Job Analysis: An Effective Management Tool. Bureau of National Affairs: Washington D.C.; Campbell, T. (July, 1982), Entry-Level Exam Examined in Court. The Western Fire Journal; Sturn, R. D. (September, 1979), Mass Validation: The Key to Effectively Analyzing an Employer's Job Classifications. Public Personnel Management.

Step 1: Assemble and train a panel of qualified Job Experts

Job Experts are qualified job incumbents who perform or supervise the target position. The following criteria are presented as guidelines for selecting the members of the panel. The Job Experts chosen should:

- Collectively represent the demographics of the employee population (with respect to gender, age, race, years of experience, etc.). It is a good idea to slightly over-sample gender and ethnic groups to insure adequate representation in the job analysis process.*

- Be experienced and active in the position they represent (e.g., Job Experts should not be on probationary status or temporarily assigned to the position). While seasoned Job Experts will often have a good understanding of the position, it is also beneficial to include relatively inexperienced Job Experts to integrate the “newcomer’s perspective.” However, at least one-year job experience should be a baseline requirement for Job Experts selected for the panel.

- Represent the various “functional areas” and/or shifts of the position. Many positions have more than one division or “work area” or even different shifts, where job duties and KSAPCs may differ.

- Include between 10 and 20% supervisors for a given position. For example, if a 7 – 10 person Job Expert panel is used, include 1 – 2 supervisors on the panel.

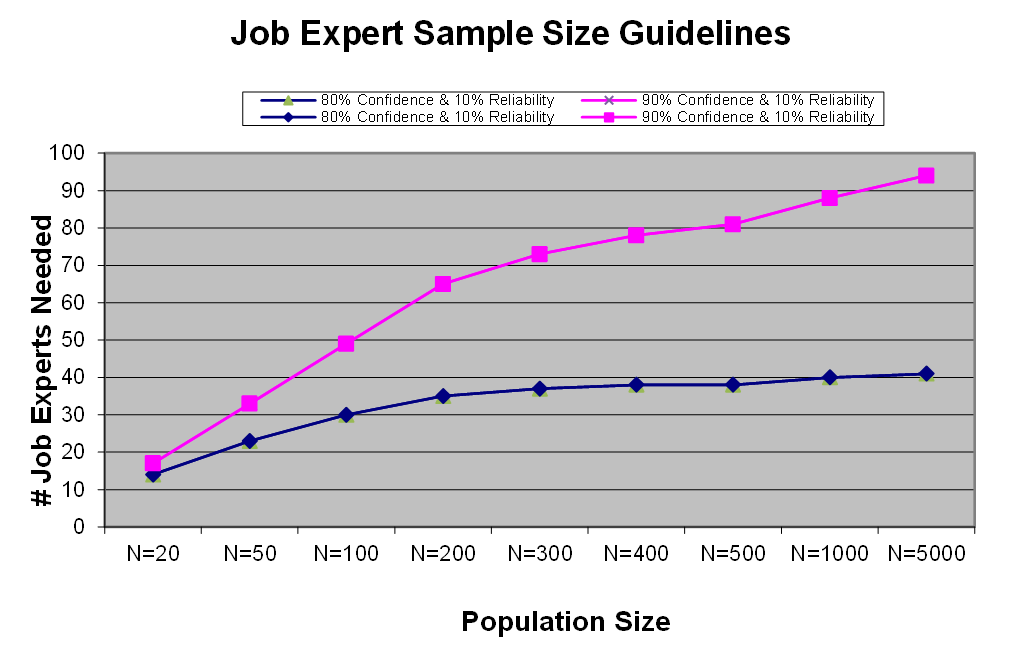

How many Job Experts are necessary to include in the job analysis process to produce reliable results? Some courts have relied on as few as 7 – 10 Job Experts** for providing judgments and ratings about job and selection procedure characteristics. Figure 2-1 provides some guidance regarding the number of Job Experts necessary to obtain a statistically reliable and accurate estimate regarding job information.

Figure 2‑1 Job Expert Sample Size Guidelines

For example, if there are currently 200 employees in a position and the employer desires to be 80% confident (with 10% “margin of error”) that the collective opinions of a Job Expert panel will accurately represent the larger population of 200 employees, about 35 Job Experts are required. Using a 90% confidence level requires about 60 Job Experts.*** Using 10 Job Experts provides about 66% (with 10% margin). While this figure and some court cases have provided guidance on this issue, practical judgment and workforce availability should be considered when assembling a panel of Job Experts.

It should be noted that there is a large “diminishing effect” that can be observed on the chart above. For example, including 80 Job Experts in a population of 400 yields very similar levels of accuracy when compared to including 100 Job Experts for a population of 5,000! The time and money that can be saved by using a “smart” rather than “huge” sampling strategy is very significant. It is not uncommon to find situations where employers unnecessarily involve hundreds and hundreds of “extra” subjects in a survey when a much smaller sample would have provided nearly identical results!

It should be noted that the GOJA Process described herein involves conducting a workshop with a Job Expert panel including 7 – 10 employees who currently hold the job. Based on the experience level of the researcher, the nature and type of the position being studied, and the Job Experts who are available, other job analysis methods may also be very useful. These include conducting structured interviews (of individual Job Experts or Job Expert panels), reviewing diaries, logs, or other work records, conducting time study analyses, administering questionnaires, or using checklists.

After designating the Job Experts who will participate in the job analysis process, they should be trained on the overall process and be informed that their responses should be both independent and confidential (i.e., not disclosed to anyone outside the job analysis Job Expert panel). Because each Job Expert’s opinion should be counted equally regardless of rank or functional job area, it is often useful to explain to the Job Experts that the job analysis workshop is a meeting “without rank.” It is important that each Job Expert’s opinion be treated with equal weight. It is also useful for the group to be aware of the limitations of possible “group think.” They should be encouraged to think independently.

* Employers who have been challenged in court for employment discrimination and who have included only majority group members in the job analysis or validation process typically have a difficult time defending themselves in court.

** Contreras v. City of Los Angeles (656 F.2d 1267. 9th Cir. 1981) and US v. South Carolina (434 US 1026, 1978).

*** Arkin, H., & Colton, R. R. (1950), Tables for Statisticians. New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc. Technical note: other sampling techniques can be useful for estimating the sample sizes necessary for estimating the average ratings for the job analysis rating scales; however, because most of the (somewhat continuous) scales are used in a dichotomous fashion (and further because the population standard deviations are unknown in each job analysis study), the population proportion formula was used for estimating these sample size requirements.

Step 2: Job Experts write Job Duties

In this step, Job Experts independently write job duties performed in the target position without providing any ratings (e.g., frequency, importance). Having Job Experts independently identify duties is an important first step in the job analysis process. This independent work–without a group or “paired” discussion–helps insure that the final combined list of duties (which is the next step) is as complete as possible. Job duties should usually begin with an action word, include the process (tasks) for completing the duty, and include the work product or outcome of the duty. For example: “Prepare correspondence using word processing software and reference documents and deliver to clients using e-mail.”

Allowing multiple, independent opinions typically allows a final duty list to be created that, after being consolidated, includes 2 – 3 times the number of duties that any individual Job Expert recorded. Depending on the complexity of the job, providing Job Experts with 1 – 2 hours to record their job duties is usually sufficient.

Step 3: Consolidate Duties into a master Duty list

After the Job Experts have independently recorded the duties of the target position, a facilitator should convene the panel and develop a master, consolidated list that reflects the majority opinion of the group. Using a 70% consensus rule (e.g., 7 out of 10) for this step is suggested or a lower ratio may be used if the job analysis results will be sent in survey form to a larger Job Expert sample. At this step, job duties from pre-existing job descriptions and other suggestions or data from management should be integrated into the discussion and added to the master list if the majority of the Job Experts agree.

Step 4: Write KSAPCs, Physical Requirements, Tools & Equipment, Other Requirements, and Standards

Have the Job Experts repeat the process described in Step 2, but for the KSAPCs, Physical Requirements, Tools & Equipment, Other Requirements, and Standards. The following definitions can be helpful for this step:

- Knowledges: A body of information applied directly to the performance of a duty. For example: Knowledge of construction standards, codes, laws, and regulations.

- Skill: A present, observable competence to perform a learned physical duty. For example: Skill to build basic wood furniture such as bookcases, tables, and benches from raw lumber, following written design specifications.

- Ability: A present competence to perform an observable duty or to perform a non-observable duty that results in a product. For example: Training ability to effectively present complex technical information to students in a formal classroom setting, using a variety of approaches as needed to maximize student learning.

- Personal Characteristics: These are characteristics that are not as concrete as individual knowledge, skills, or abilities. Examples include “dependability,” “conscientiousness,” or “stress tolerance.” The Uniform Guidelines do not permit measuring abstract traits in content-validated selection process (see Section 14C1) unless they are clearly operationally defined in terms of observable aspects of job behavior.* For example, while the characteristic “dependability” (if left undefined) is too abstract to directly measure in a selection process, if it can be defined as “promptness and regularity of attendance,” which is an observable work behavior, it can be measured. “Stress tolerance,” if not clearly operationally defined, is also too abstract for inclusion in a selection process under a content validity approach. However, if defined as “the ability to complete job duties in a timely and efficient manner while enduring stressful or adverse working conditions,” it is converted into an essential work ability that is readily observable on the job. So, if one desires to include personal characteristics in the selection process, turn them from abstract ideas to concrete, observable skills and abilities.

Physical Requirements, Other Requirements, and Standards will vary greatly between jobs. Several existing taxonomies are available—see the GOJA Manual included in the Evaluation CD for several examples of each.

* See Section 14C1 and 14C4 of the Uniform Guidelines and Questions & Answers # 75.

Step 5: Consolidate KSAPCs, Physical Requirements, Tools & Equipment, Other Requirements, and Standards into a master list

For this step, the Job Experts repeat the process described in Step 3, but for the KSAPCs, Physical Requirements, Tools & Equipment, Other Requirements, and Standards. As in Step 3, the KSAPCs, Physical Requirements, Tools & Equipment, Other Requirements, and Standards from pre-existing job descriptions and other suggestions or data from management can be included in the process.

Step 6: Have Job Experts provide ratings for Duties, KSAPCs, and Physical Requirements

The Job Experts and supervisors can provide ratings now that a final list of duties and KSAPCs has been compiled. For Job Duties, Job Experts can provide the following ratings (see the GOJA Manual for sample rating scales):

- Frequency of performance: How frequently is the Job Duty performed? Daily? Weekly? This is not a requirement under the Uniform Guidelines for content validity, but it is useful for several practical reasons (note, however that it is required for criterion-related validity studies!). One of the useful purposes for this rating is for determining which job duties constitute essential functions under the Americans with Disabilities Act (Section 1630.2[n][3][iii]).

- Importance: How important is competent performance of the Job Duty? What are the consequences if it is not done or done poorly? The importance rating is perhaps one of the most critical ratings that Job Experts provide. Section 14C2 of the Uniform Guidelines states that the duties selected for a selection procedure (e.g., a work sample test) “. . . should be critical work behavior(s) and/or important work behavior(s) constituting most of the job.” Thus, the Uniform Guidelines are clear that when using content validity for a work sample test, the selection procedure can be linked to a single critical duty (“critical” is later defined by the Uniform Guidelines as “necessary”), or several important duties that constitute most of the job.

For KSAPCs and Physical Requirements, Job Experts can rate:

- Links to Duties: Where is this KSAPC/Physical Requirement actually applied on the job? What are the Job Duties (by duty number) where it is used? This step is key for establishing content validity evidence. By linking the duties to the KSAPCs and Physical Requirements, a nexus is created showing where actual job skills (for example) are actually applied on the job. Completing this step addresses Section 14C4 of the Uniform Guidelines.

- Frequency: How often is this KSAPC/Physical Requirement applied on the job? While it is a good idea to obtain a direct rating from Job Experts on this factor, this question can also be answered by determining the Job Duty with the highest frequency rating to which the KSAPC/Physical Requirement is linked.

- Importance: How important is the KSAPC/Physical Requirement to competent job performance? This is perhaps the most important rating in a content validity study because the Uniform Guidelines require that a selection procedure measuring a KSAPC/Physical Requirement should be shown to be a “necessary prerequisite” of “critical or important work behaviors” and shown to be “used in the performance of those duties” (Sections 14C4 and 15C5). Because the Uniform Guidelines make this clear distinction between only “important” and “critical or necessary,” the importance rating scale should take this into consideration by making a clear demarcation in the progression of importance levels between important and critical. A selection procedure measuring KSAPCs/Physical Requirements should be linked to critical and/or important work duties, and should be rated as “critical” or “necessary” by Job Experts.

All Job Experts who participated in the job analysis process can provide ratings; however, in Step 7, using only two supervisors is sufficient for providing the supervisor ratings. Calculating inter-rater reliability and removing outliers* from the data set can be a useful step for insuring that the raters are providing valid ratings.

After all ratings are collected, they should be reviewed for accuracy and completeness, and then averages for each Job Duty and KSAPC rating should be calculated. This should be performed before proceeding further because supervisors will consider the rating averages in subsequent steps.

* Eliminating ratings (not raters, but only their ratings that have been identified as outliers) using a 1.645 standard deviation rule (all ratings that are 1.645 standard deviations above or below the mean are deleted) is one way of completing this step. Using this criteria will serve to “trim” the average ratings that are in the upper or lower 5% of the distribution.

Optional step for positions with a large numbers of incumbents: distribute a Job Analysis Survey (JAS) to additional Job Experts for ratings

Completing the six steps above results in a completed job analysis that represents the collective and majority opinions of the 7 – 10 Job Experts included in the process. While including 7 – 10 Job Experts in the process is likely to provide accurate and reliable information about a position for many employers, increasing the Job Expert sample size will increase the accuracy and reliability of the information about the position (if there are more than ten Job Experts in the position).

Obtaining the opinions of additional Job Experts can be completed using a Job Analysis Survey (JAS). A JAS can be prepared by providing the duties, KSAPCs, and Physical Requirements in survey form to the Job Experts and having the Job Experts rate the “content” of each, in addition to all other standard “job-holder ratings.” For example, Job Experts can use the following scale in a JAS for rating each duty:

This duty is (select one option from below) a duty that I perform.

- Not at all similar to (does not describe)

- Somewhat similar to (some of the objects listed and actions described in the duty are somewhat similar to the objects and actions in the duty performed in your job)

- Similar to (most of the objects listed and actions described in the duty are similar to the objects and actions in the duty performed in your job)

- The same as (Extremely similar or exactly like)

Job Experts can use the following scale to rate each KSAPCs and Physical Requirements:

This KSAPC / Physical Requirement is (select one option from below) a KSAPC / Physical Requirement I apply on the job.

- Not at all similar to (does not closely describe)

- Somewhat similar to (somewhat describes)

- Similar to (closely describes)

- The same as (very accurately describes)

One potential benefit of providing the additional Job Expert group with a JAS is that the additional Job Experts may know of other legitimate Job Duties, KSAPCs, or Physical Requirements that are required for the position, but were not identified by the original Job Expert group. It is suggested to provide extra space on the JAS where the additional Job Experts can record and rate additional duties, KSAPCs, and/or Physical Requirements they identify while completing the JAS.

It is recommended to use 3.0 as the minimum average-rating criteria for these two ratings when deciding whether to include a duty or KSAPC/Physical Requirement in a final job analysis.

Step 7: Have two supervisors review the completed job analysis and assign supervisor ratings

After the final job duty, KSAPC, and Physical Requirements have been rated by the Job Experts and the ratings have been averaged, convene two supervisors (these supervisors may have participated in the first six steps of the process, or can be new to the GOJA Process) to assign the “Supervisor Only” job analysis ratings. The ratings that supervisors should provide for Job Duties include:

- Percentage of Time: When considering all Job Duties, what percentage of a typical incumbent’s time is spent performing this Job Duty? Evaluating the percentage of time that incumbents spend on a particular duty is one of several factors that should be considered when making essential function determinations under the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (Section 1630.2[n][3][iii]). While helpful, it is not absolutely required for content validation studies.

- Best Worker: What Job Duties distinguish the “minimal” from the “best” worker? Job Duties that are rated high on the Best Worker rating are those that, when performed above the “bare minimum,” distinguish the “best” performers from the “minimal.” For example, lifting boxes and occasionally helping guests with luggage may be necessary for a hotel receptionist position. However, performing these job duties at a level “above the minimum” will not likely make any difference in a person’s overall job performance. It would likely be other Job Duties such as “greeting hotel guests and completing check-in/check-out procedures in a timely and friendly fashion” that would distinguish between the “minimal” and the “best” workers for this job. The average rating on this scale can provide guidance for using a work sample type of content validity selection procedure on a pass/fail, ranking, or banding basis (see Section 14C9 of the Uniform Guidelines). It is not necessary to obtain this rating for Job Duties unless the employer desires to validate a work sample type of selection procedure (i.e., a selection procedure that relies on linkages to Job Duties and not necessarily KSAPCs).

- Fundamental: How fundamental is this Job Duty to the purpose of the job? Would the position be fundamentally different if this Job Duty was not required for performance? Handcuffing suspects is fundamental to the job of Police Officer. Rescuing victims is fundamental to the firefighter job. Fundamental Job Duties are duties that constitute “essential functions” under the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (this rating is helpful, but not necessary for validation). A Job Duty may be considered fundamental to the job in any of the following ways:

- The duty is frequently performed (check the Frequency rating) and/or the proportion of work time spent on it is significant (check the average Percentage of Time rating), or

- The consequence to the purpose of the job is severe if the Job Duty is not performed or if it is performed poorly (check the average Importance rating), or

- Removing the Job Duty would fundamentally change the job. In other words, the duty is fundamental because the reason the job exists is to perform the duty, or

- There are a limited number of employees available among whom the performance of this Job Duty can be distributed, or

- The duty is highly specialized and the incumbent was placed in the job because of his/her expertise or ability to perform this particular Job Duty.

- Assignable (Assignable to Others): Can this Job Duty be readily assigned to another incumbent without changing the fundamental nature of the position? In such instances, the Job Duty should not be considered as an “essential function” under the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act. For example, a Job Duty can be determined to be fundamental (using the “fundamental duty” rating) and hence also “essential” under the ADA; however, if such Job Duty can be readily assigned to another employee without changing the fundamental nature of the job, the Job Duty can be re-designated as not essential. Job Duties which are frequently performed or which take up a large proportion of work time and which are important or critical, probably are not easily assigned to others. Duties which occur infrequently and/or which require a small percentage of work time can sometimes be assumed by others, regardless of how important or unimportant they are.

For KSAPCs and Physical Requirements, supervisors can rate:

- Minimum v. Helpful Qualifications: Is this KSAPC/Physical Requirement a necessity for the position? Or, while possibly helpful to the performance of the job, is it an absolute requirement? This rating can help determine which KSAPCs/Physical Requirements should be included in a selection process. Minimum qualifications are those that the applicant or candidate must have prior to entry into the position; helpful qualifications can still be included in the selection process (if they meet the other requirements discussed herein), but are not absolute necessities prior to entry.

- Level Needed for Success (for Job Knowledges Only). What level of this job knowledge is required on the first day of the job? Total, complete mastery? General familiarity? The data from these ratings are useful for choosing the job knowledges that should be included in a written job knowledge test (see Section 14C4 of the Uniform Guidelines for specific requirements for measuring job knowledge in a selection process).

- Level Needed Upon Entry: How much of this KSAPC/Physical Requirement will be required on the first day of the job? All? Some? None? Will some on-the-job training be provided, or will candidates be required to bring all of this KSAPC/Physical Requirement with them on the first day of the job, with no additional levels attained after hire? This rating provides direction on which KSAPCs/Physical Requirements to screen in a selection process. This is a requirement of the Uniform Guidelines (Section 14C1).

Step 8: Prepare final job analysis document, including descriptive statistics for ratings

After compiling the Job Expert and supervisor rating data, a report should be compiled that provides descriptive statistics (e.g., means and standard deviations) for each rated item. The final data (e.g., Job Duties, KSAPCs, etc.) can be entered directly into the job analysis document, along with the means and standard deviations that accompany each, to compile a final job analysis for a position.

Developing a Selection Plan

Now that a thorough job analysis has been developed, a Selection Plan is the next step in the content validation process. Completing a Selection Plan is the step in the validation process where the key, measurable KSAPCs and Physical Requirements are laid out as targets to be assessed by the selection process. A Selection Plan distills the complete list of KSAPCs and Physical Requirements into only those that can and should be tested by one or more selection procedures in the overall selection process. Thus, it begins with every KSAPC/Physical Requirement produced through the job analysis, and ends with a list of fewer KSAPCs/Physical Requirements after running each through the stepwise “Selection Plan screening process.” This process uses the average KSAPC/Physical Requirement ratings provided by Job Experts, as shown below:

- Importance: Select only the KSAPCs/Physical Requirements that are above a certain level on the Importance rating scale. It is usually sufficient to draw the line at one-half (0.5) a rating point above the level on the rating scale that distinguished between the “important” versus “critical and necessary” (e.g., require an average rating of 3.5 if 3.0 is “important” and 4.0 is “critical”). This is important because the KSAPCs/Physical Requirements selected for measurement should be those that are most critical for success on the job (see Section 14C4 of the Uniform Guidelines). It is possible to develop a valid selection procedure for measuring only “important” (not necessary) KSAPCs if they “constitute most of the job” (see Section 14C4 of the Uniform Guidelines).

- Level Needed Upon Entry: Select only the KSAPCs/Physical Requirements that are above a certain level on this rating scale. Establish the criteria the point on the rating scale where more than one-half (51% +) of the level needed is required on the first day of the job. This step is important because the KSAPCs/Physical Requirements selected for measurement should be those that needed upon entry to the job (see Sections 5F and 14C1 of the Uniform Guidelines).

- Level Needed (Knowledges only): Select only the Job Knowledges that are required (on the first day of the job) at a “working” or “mastery” level. This step helps avoid measuring job knowledges that are not critical for job success, or can easily be looked up without a negative impact on the job. This step is only required if job knowledge tests will be included in the selection process, and is required to address Section 14C4 of the Uniform Guidelines.

- Minimum/Helpful Qualification (MQ/HQ): While it is possible to measure KSAPCs/Physical Requirements that are Helpful Qualifications and not absolutely “minimum” (if they meet the other steps above), it is typically a good idea to focus primarily on those that are absolutely necessary for the job (i.e., are MQs).

- Best Worker: Rank order the remaining KSAPCs/Physical Requirements (i.e., those that met the criteria above) from highest to lowest using the average Best Worker rating. This will place the “best predictors” for selecting the best workers at the top of the list.

After this five-step process has been used to filter the KSAPCs/Physical Requirements, conduct a meeting with the Job Experts and the Supervision/Management staff and discuss the selection procedures that have been used in previous selection processes and those that can possibly be used for future selection processes. Then allow them input to choose which selection procedures will be used in the next selection process and how each will be used (pass/fail, ranked, or weighted and combined with other selection procedure—see relevant sections within BCGi Resources for a discussion of the various criteria for each). At a minimum, rank only on selection procedures that are among the highest on the Best Worker ratings, or those that received absolute ratings that were sufficiently high to justify ranking).

The following factors should be discussed when deciding which selection procedures to use, and how to use them (listed in priority order):

- Which selection procedures were most effective in selecting the most qualified incumbents? While a criterion-related validity study is required to answer this question definitively, management judgment can be used in most situations. Which proposed (but not yet used) selection procedures do we believe are most likely to screen in the best workers? What have similar employers used successfully? The reliability of the selection procedures can also be considered at this step (see relevant BCGi Resource pages for a discussion on reliability).

- What degree of adverse impact did the previous selection procedures have against women and minorities? How does this weigh against the perceived level of effectiveness of these selection procedures? Are there alternatives that would have less adverse impact, but be substantially equally valid? (Section 3B of the Uniform Guidelines requires that employers make this consideration when using a selection procedure that has adverse impact).

- Which selection procedures are easiest to administer? Which take the longest time to complete and score? For example, a written test can be administered to 1,000 applicants with much less time and administrative efforts than an interview involving multiple rater panels.

- What are the costs of the selection procedures? Notice that this factor is last on the list. When making selection decisions that impact the overall performance of an employer, the careers and livelihoods of individuals, and impact the social community as a whole, other factors should be considered above cost whenever possible.

Table 2-1 below provides an example of what this five-step process will produce:

.png)

Table 2‑1 Selection Plan Example

Notice that the KSAPCs in Table 2-1 are ranked from top to bottom based on their average Best Worker rating assigned by Job Experts. Reproducing all of the relevant KSAPC ratings allows management to make informed decisions on if and how each will be assessed in the selection process.

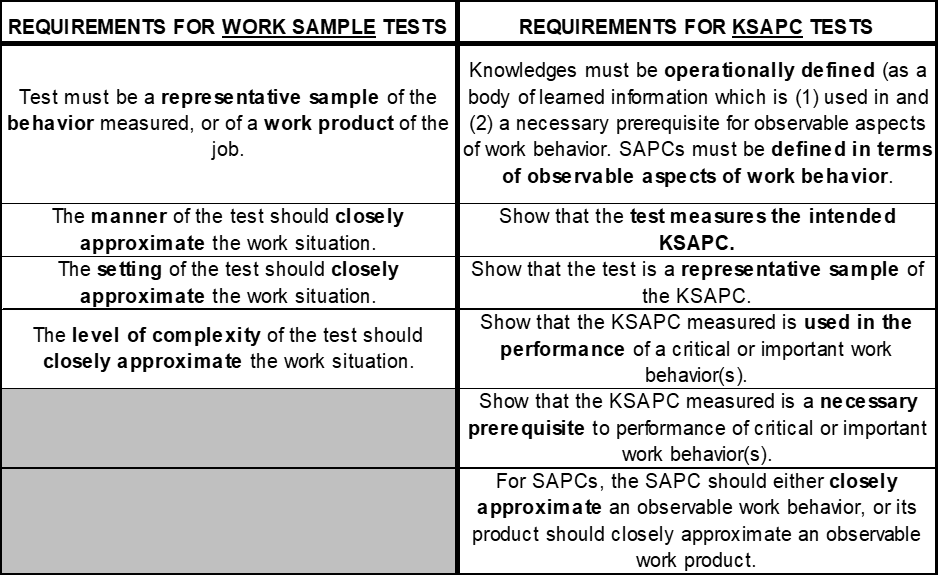

Content Validation Requirements for "Work Sample" and "KSAPC" Types of Selection Procedures

The Uniform Guidelines present different criteria for validating “work sample” tests (i.e., tests that attempt to directly mirror or replicate one or more job duties) and KSAPC tests (i.e., tests that measure KSAPC without necessarily directly mirroring or replicating the job). Table 2-2 shows these requirements by type of test:

Table 2‑2 Content Validity Requirements for Work Sample and KSAPC Tests

Section 14C1 of the Uniform Guidelines states:

Selection procedures which purport to measure knowledges, skills, or abilities may in certain circumstances be justified by content validity, although they may not be representative samples, if the knowledge, skill, or ability measured by the selection procedure can be operationally defined as provided in paragraph 14C(4) of this section, and if that knowledge, skill, or ability is a necessary prerequisite to successful job performance.

This clarification is needed because sometimes content valid selection procedures that measures KSAPCs do not necessary resemble or “closely approximate” the job. Consider reading ability, for example. Reading ability might be a critical, “needed on day one” requirement for the position of Police Officer, but reading ability can be measured in a valid way without having the applicant read and take a written test on police-related information. In fact, the reading ability of applicants applying for the police department could be measured by having the applicants read a 10-page narrative (written at a grade level needed for success as a police officer) about basket weaving and answer questions to demonstrate adequate comprehension. While basket weaving has absolutely nothing to do with the job of police officer, consider how such a test sizes up to the KSAPC test requirements shown in Table 2-2:

Does the basket weaving reading comprehension test:

- Measure an ability (reading) that is defined in terms of observable aspects of work behavior? Yes, provided that the reading ability in the Job Analysis (to which this test is linked), is linked to job duties that are observable.

- Measure the intended KSAPC (reading ability)? Yes, provided that the test measures reading ability at the level necessary for the job.

- A representative sample of the KSAPC (reading ability)? Yes, provided that the sentence structure and readily level are similar. Police officers are likely to read 10 pages or less with certain levels of comprehension necessary.

- Measure a KSAPC that is used in the performance of a critical or important work behavior(s)? Yes, provided that reading ability is linked to critical or important Job Duties.

- Measure a necessary prerequisite to performance of critical or important work behavior(s)? Yes, provided that reading ability has been rated sufficiently high on the importance scale used.

- Closely approximate an observable work behavior, or does its product closely approximate an observable work product? Yes, a police officer can be observed reading and studying new laws, bulletins, etc.

Now, would it be a better idea to administer a reading ability test that used content that was similar in content to the job? Yes, the more closely the content of the test represents the job, the better! This adds to the face validity of the process and helps improve applicants’ perception of the fairness of the process as a whole. As such, the example above is provided for illustration purposes only. One could certainly make a case for using sample job material (e.g., sample police policies and procedures, vehicle traffic codes, etc.) because the psychological processes of comprehending this type of material may be slightly different than those used when learning about basket weaving (e.g., especially if one type was more or less abstract or concrete than the other).

Next, consider a test event commonly found in physical ability tests for the position of firefighter called a “Dry Hose Advance.” This event is one of several events in a test used to screen applicants for the position of entry-level firefighter. To take the test, applicants are required to wear firefighter protective clothing (including pants, coat, gloves, and a 20-pound breathing apparatus) since this is how the event is performed on the job. This event measures the applicant’s ability to take a dry (not charged with water) 1-1/2 inch fire attack hose line from a fire truck and extend the hose 150-feet (which simulates taking the hose line from the truck and deploying it to the position where it will be used to attack the fire).

Does this test event mimic the job? Yes—almost exactly (and as best as can be hoped for without lighting an actual fire). When linking this event back to the Job Analysis (to complete the essential nexus necessary for content validity), where does it fit? Is this a work sample or a KSAPC test? It is clearly a work sample test. Consider how this test fares when running it through the criteria shown in Table 2-2 for work sample tests:

Is the Dry Hose Advance test:

- A representative sample of the behavior measured, or of a work product of the job? Yes, clearly. Firefighters perform this exact same event, even for a similar distance, while performing it on the job. The only difference on the job is the fire and the smoke that may be present.

- Conducted in a manner that closely approximates the work situation? Yes, the physical movements and actions in this test event are done in a way that very closely approximates the work situation, and does not require specialized training.

- Conducted in a way that the setting of the test closely approximates the work situation? Yes, both the test and the actual job duty it simulates are done outside, by one person, using a “transverse hose bed” and are done in a way where speed is of the essence.

- Conducted in a way that the level of complexity of the test closely approximates the work situation? Yes, the test is not too difficult or easy compared to the job. It is about the same.

This example is intended to show that work sample tests—more so than KSAPC tests—need to be specific about such factors as “how long,” “how heavy,” “how far,” “how difficult,” etc.