BCG InstituteBCGi

Developing, Validating, and Analyzing Written Tests

While many types of selection procedures are frequently litigated, none are as vulnerable as the infamous written test. There are at least two reasons for this. First, written tests typically have higher levels of adverse impact against minorities (Sackett, 2001; Neisser, 1996) than other types of selection procedures, making them eligible for civil rights litigation. Second, they are sometimes only theoretically related to the job, or not sufficiently related to the job. Despite these drawbacks, written tests are frequently valid predictors of job success and are typically not biased against minorities (Principles, 2003, p. 32).

For these reasons, employers should complete validation studies on written tests. Completing a thorough validation process helps insure that the test used for selection or promotion is sufficiently related to the job (and includes only test items that Job Experts have deemed fair and effective) and generates documentation that can be used as evidence should the test ever be challenged in an arbitration or civil rights litigation setting.

It would be difficult if not impossible to create a step-by-step instruction guide for developing and validating all of the different types of written tests that are commonly used by employers. Because test content varies based on the types of knowledgees, skills, abilities, and personal characteristics (KSAPCs) measured, the level they are measured (e.g., entry-level testing versus promotional), and the purpose of the test (e.g., employment, licensing, credentialing, etc.) this becomes an even more difficult task.

This section of BCGi Resources is designed to provide a basic blueprint that can be followed for developing and validating some of the most commonly used tests by employers, such as:

- Mechanical ability

- Cognitive ability

- Situational judgment

- Reading comprehension

- Math skills

- Job knowledge

- Problem solving/decision making skills

This section of BCGi Resources assumes that the reader will be using a conventional written test format (e.g., multiple choice questions) to measure KSAPCs that are necessary for entry-level or promotional testing purposes. While some of the content herein is relevant for educational and/or credentialing or licensure tests, it is not designed to specifically address these testing situations.

Steps in Written Test Development

The following steps can be followed to develop and validate most written tests that will measure KSAPCs needed for the job.

Step 1: Determine the KSAPCs to be measured by the test

The Selection Plan described in this section of BCGi Resources can be used for selecting the KSAPCs that can be measured by the written test. If a Selection Plan has not been completed, consider using the criteria below (as baselines). The KSAPCs selected for the written test should be:

- “Needed day one” on the job;

- Important or critical (necessary) for the performance of the job;[i]

- Linked to one or more critical (necessary) job duties; and

- For job knowledges only, rated sufficiently high on the “Level Needed for Success” rating (see the Job Analysis Section in BCGi Resources). This is necessary for insuring that the job knowledge domains measured by the test are needed (on the first day of hire) at a level that requires the applicant to have the information in memory (written tests should not measure aspects of a job knowledge that can simply be looked up or referenced by incumbents on the job without serious impacting job performance).

It is important to note the KSAPC selected for measurement on the written test should meet these criteria both generally (i.e., as defined in the job analysis) and specifically (i.e., the separate facets or aspects of the selected KSAPCs should also meet these criteria). For example, if “basic math” is required for a job and it meets the criteria above, test items should not be developed for measuring advanced math skills.

[i] If the test will be used to rank applicants, or a pass/fail cutoff that is above minimum competency levels will be used, the “Best Worker” rating should also be used as a minimum criteria, with a minimum level set for selecting KSAPCs for the test (see BCGi Resources).

Step 2: Develop a test plan for measuring the selected KSAPCs

There are three areas that should be addressed for developing a solid written test plan:

- General components of a test plan;

- Choosing the number of test items; and

- Choosing the types of test items.

Each of these areas is discussed below.

General components of a test plan

The elements and steps necessary for a written test plan will vary based on the types of KSAPCs measured by the test. The components below should therefore be regarded as general requirements:

- What is the purpose for the test? Will it be used to qualify only those who possess mastery levels of the KSAPC? Advanced levels? Baseline levels?

- Will the test be scored in a multiple hurdle or compensatory fashion? Multiple hurdle tests require applicants to obtain a passing score on each section of the written test. Compensatory tests allow an applicant’s high score in one area to compensate for an area in which they scored low. A multiple hurdle strategy should be used if certain, baseline levels of proficiency are required for each KSAPC measured by the test; a compensatory approach can be used if the developer will allow higher levels of one KSAPC to compensate for another on the test. Evaluating how the KSAPCs are required and used on the job is a key consideration for making this decision.

- What is the target population being tested? Has the applicant population been pre-screened using minimum qualification requirements?

- Will the test be a speeded test or a power test? A test is considered a speeded test when time is considered an element of measurement on the test (for reasons that are related to the job) and it is not necessary to allow the vast majority of applicants to complete the test within the time limit (some tests based on criterion-related validity are designed with speed as an essential component of the test). A power test allows at least 95% of the applicants to complete the test within the allotted time. Most written tests are administered as power tests.

- What reading level will be used for the test? Most word processing programs include features for checking the grade reading level of the test, which should be slightly below the reading level required at entry to the job.

- What will be the delivery mode of the test (e.g., paper/pencil, oral, computer-based testing)?

- What scoring processes and procedures will be used?

- Will a test preparation or study guide be provided to applicants? Test preparation and study guides can be developed at many levels, ranging from a cursory overview of the test and its contents to an explicit description of the KSAPCs that will be measured.

- Will test preparation sessions be offered to the applicants?

Choosing the number of test items

Some of the key considerations regarding selecting the number of items to include on the written test are:

- Making an adequate sampling of the KSAPC measured. A sufficient number of items should be developed to effectively measure each KSAPC at the desired level. Note that some KSAPCs will require more items than others for making a “sufficiently deep” assessment of the levels held by the applicants. Be sure that the important aspects of each KSAPC are included in the test plan.

- Making a proportional sampling of the KSAPCs. This pertains to the number of items measuring each KSAPC compared with others. The test should be internally weighted in a way that insures a robust measurement of the relevant KSAPCs (this is discussed in detail below). Special consideration should be given to this proportional sampling requirement when developing job knowledge tests (see the TVAPÒ User Manual in the Evaluation CD for a sample test plan for job knowledge tests).

- Including a sufficient number of items to generate high test reliability. While there are numerous factors that impact test reliability, perhaps the single most important factor is the number of test items per relevant KSAPC and in the test overall.

There are no hard-and-fast rules regarding the number of items to include for measuring a KSAPC. A developer can have few or many test items for any “testable KSAPC” (those that meet the criteria above); however, some rational or empirical process for internally weighting the written test is helpful and usually makes the test more effective. Here are some guidelines to consider:

- Some KSAPCs are more complex or broad than others, and thus may require more test items for adequate measurement. For example, finding out how much an applicant knows about advanced physics may require more items than assessing their simple multiplication skills, which can be assessed with fewer items.

- If several discreet KSAPCs will be measured on the same written test, be sure that they are not divergent. If they are, put them on separate tests (or on the same test as a subscale that is scored separately). If the test will be scored and used as one, overall assessment (i.e., with one final score for each applicant), the various KSAPCs on the test will need to be homogeneous (i.e., having similar types of variance because they are based on similar or inter-related content and items of similar difficulty levels). If one KSAPC is substantially different from others on the same test, the test items will be working against each other and will decrease the overall reliability (making the interpretation of a single score for the test inaccurate).

- As a general rule, do not measure a discreet KSAPC with fewer than 20 items, and be sure that the overall test includes at least 60 items if measuring more than one KSAPC. This will help insure that the test will have sufficiently high reliability.

One of the factors for choosing the number of items to include on the test (and from which KSAPCs) is to internally weight the test in a way that is relevant to the requirements of the job. One effective system for developing internal weights for a test is to have Job Experts assign point values to the various sections of the test. For example, if there are five different KSAPCs measured by the test, the Job Expert panel can be asked to assign 100 points among the five KSAPCs to come up with a final weighting scheme for the test.

The drawback to using this approach is that the items will now require polytomous weighting (e.g., 0.8 points for the items measuring Skill A, 1.2 points for each item measuring Skill B, etc.). This can be avoided by simply adding or removing the number of items to each section as necessary to match the test weighting provided by Job Experts, being careful not to have too few items on any given section.

Choosing the type of test items

What type of test items should be included on the test to measure the KSAPCs? Complex? Easy? Difficult? When measuring job knowledge domains, should items be included that measure the difficult, complex, evaluative aspects of the knowledge, or just the simple facts and definitions? The key consideration regarding selecting the type of items for a test is making sure that the KSAPCs are measured in a relevant way using items that are appropriately geared to the level of the KSAPC that is required on the job.

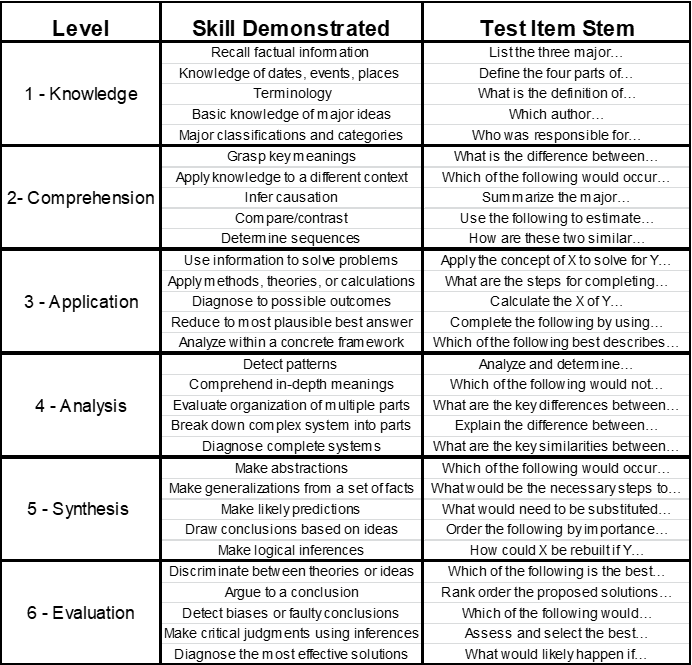

One helpful tool for making item type considerations is Bloom’s Taxonomy (1956), which can be adopted as a model for developing written test items that measure the intended KSAPC at various levels.

Table 3‑1 Bloom's Taxonomy for Item Writing

Test developers can use this Taxonomy (or an abbreviated version) to provide guidance for developing items that are at an appropriate level for the job (considering how the KSAPC is applied on the job—e.g., factual recall, application, analysis, etc.).

Another factor to consider regarding the item type is the format of the item. Common formats include multiple choice, true/false, open-ended, or essay. Multiple choice is perhaps the most common format used for fixed-response items (items with only a limited number of alternatives), and for a good reason. Applicants have a 50% likelihood of guessing the correct answer for true/false items, and only 25% likelihood for multiple choice items with four alternatives (or 20% likelihood for items with five alternatives).

Open-ended and essay formats require subjective scoring, which can be timely and costly. Another drawback with these formats is that another type of unreliability enters into the equation when the tests are scored: inter-scorer reliability. Inter-scorer reliability relates to the consistency between scorers who subjectively grade the tests. While there is nothing wrong with these types of item formats (in fact they are the best item formats to use for the higher level of Bloom’s Taxonomy), they will not be discussed further in this text for the reasons stated above.

Step 3: Develop the test content

Test items can be developed by personnel professionals and/or Job Experts. If Job Experts are used, begin at Step 1; if experienced test developers are used, begin at Step 6:

- Select a panel of 4 – 10 Job Experts who are truly experts in the content area and are diverse in terms of ethnicity, gender, geography, seniority (use a minimum of one year of experience), and “functional areas” of the target position. Supervisors and trainers can also be included.

- Review the Selection Plan (see relevant section in BCGi Resources), test plan (see above), and Validation Surveys (discussed below) that will be used to validate the test. This step is critical because the Job Experts should be very well informed regarding the KSAPCs measured by the test (and their affiliated job duties), and the number and types of items to be included on the test.

- Have each Job Expert review and sign a confidentiality agreement. Along with this agreement, create an atmosphere of confidentiality and request that no documents or notes are taken out of the workshop room. Lock the doors when taking breaks.

- Conduct a training session on item writing (various guidelines are available for this.

- The training should conclude with an opportunity for Job Experts to write sample test items and then exchange and critique the items using the techniques learned in the training.

- Write test items following the Selection Plan and test plan. Be sure that item writers reference the Validation Survey that will be used by the validation panel to be sure that the items will address the criteria used by this panel for validating the items. When determining the number of items to write according to the test plan, double the number of items that are slated for measuring each KSAPC. This is necessary because the validation process will screen out some of the items and extra items that survive the validation process may be necessary for future selection processes to replace items that show poor item statistics. A Test Item Form should be used by item writers to record the KSAPC measured, correct answer, textual reference including distractor references (for job knowledge items), and other useful information for each draft item.

- Have the item writers exchange and critique items, paying careful attention to:

- Grammar, style and consistency;

- Selection Plan and test plan requirements, and

- Criteria on the validation survey

- Never be afraid to delete a poor item early in the development/validation process! It is better to keep only the best items at this phase in the process.

- Create a final version of the draft test that is ready for review by the validation panel. This version of the test should include the item, KSAPC measured, correct answer, and textual reference with distractor references (for job knowledge items).

Step 4: Validate the test

Validating a written test requires convening a group of qualified Job Experts (see criteria above for selecting these individuals) and having them review and rate the written test using several factors. Some of these factors include the quality of the test items, fairness, relationship to the job, and proficiency level required. A suggested list of rating questions that can be used is provided below (see the TVAPÒ software in the Evaluation CD for a Validation Survey that includes these survey questions):

- Regarding the quality of the test item, does the item:

- Read well? Is it clear and understandable?

- Provide sufficient information to answer correctly?

- Contain distractors that are similar in difficulty? Distinct? Incorrect, yet plausible? Similar in length? Correctly matching to the stem?

- Have an answer key that is correct in all circumstances?[i]

- Provide clues to other items on the test?

- Ask the question in a way that is free from unnecessary complexities?

- Ask the question in a way that is fair to all groups?

- Regarding the job relatedness of the item, is the item:

- Linked to an important or critical KSAPC that is needed the first day of the job?

- Linked to an important or critical job duty (Job Experts should identify this using Job Duty numbers from the Job Analysis) (Note: if the KSAPCs measured by the test have been linked to essential Job Duties, this step is not required, but can be helpful).

- Regarding the proficiency level required for the KSAPC measured by the item, what percent of minimally qualified applicants would Job Experts expect to answer this item correctly? (This data can be used for setting validated cutoff scores—see relevant section in BCGi Resources).

- For job knowledge tests:

- Is the item based on current information?

- Does it measure an aspect of job knowledge that must be memorized?

- How serious are the consequences if the applicant does not possess the knowledge required to answer this item correctly?

Validation criteria for test items

There are no firm minimum criteria that specifically apply to any of the key validation factors offered in the Uniform Guidelines or in the professional standards. In fact, it is quite possible to have a written test that could be considered as an “overall valid” selection procedure, but include several items that would be rated negatively on the ratings proposed above. However, the goal is to have every item address these criteria.

There are a few seminal court cases that can provide guidance on some of these key validation criteria. Two of these high-level court cases are Contreras v. City of Los Angeles (1981) and US v. South Carolina (1978). Because of the transportable concepts regarding written test validation that have been argued and decided in these cases, they have also been frequently referenced in other cases involving written tests. Because the judges in each of these cases ended up supporting the development and validation work surrounding the tests involved, they are worth discussing briefly here.

In the Contreras case, a three-phase process was used to develop and validate an examination for an Auditor position. In the final validation phase, where the Job Experts were asked to identify a knowledge, skill, or ability that was measured by the test item, a “5 out of 7” rule (71%) was used to screen items for inclusion on the final test. After extensive litigation, the Ninth Circuit approved the validation process of constructing a written test using this process.

In the South Carolina case, Job Experts were convened into ten-member panels and asked to provide certain judgments to evaluate whether each item on the tests (which included 19 subtests on a National Teacher Exam used in the state) involved subject matter that was a part of the curriculum at his or her teacher training institution, and therefore appropriate for testing. These review panels determined that between 63% and 98% of the items on the various tests were content valid and relevant for use in South Carolina. The US Supreme Court endorsed this process as “sufficiently valid.”

These two cases provide useful guidance for establishing the minimum thresholds (71% and 63% respectively) necessary for Job Expert endorsement necessary (at least on the job relatedness questions) for screening test items for inclusion on a final test. It is important to note that in both of these cases at least an “obvious majority” of the Job Experts was required to justify that the items were sufficiently related to the job to be selected for the final test.

Step 5: Score and analyze the test

Several years ago, I attended a two-day seminar on advanced statistical analyses for tests. There were at least 50 attendees—many with advanced degrees in statistics and testing. Almost no one understood the seminar content. For two days, the trainer spouted formulas and concepts that were supposedly useful for investigating the little nuances about tests and item analyses, but most people were just plain “missing it.” To make matters even worse, the concepts and techniques they were proposing, while useful to the very advanced practitioner, would provide little practical benefit over the classical test analysis tools that practitioners have been using for decades! Have we progressed? Maybe some, but the important part of progression is breaking down the theoretical into something that the average practitioner can actually use in everyday work.

It is the intention of this section to achieve this goal. While there is no escaping the fact that test analysis requires the use of advanced statistical tools, some of these can be automated by software tools. Many of them can be completed in common spreadsheet programs. The purpose of this section is to equip the reader with a basic knowledge of many fundamental, essential components of test analysis, and (most importantly) interpretation rules than can be applied to look for problem areas.

Classical test analysis [ii] (conducted after a test has been administered) can be broken down into two primary categories: item-level analyses and test-level analyses. Item-level analyses investigate the statistical properties of each item as they relate to other items and to the overall test. Test-level analyses focus on how the test is working at an overall level. Because the trees make up the forest, the item-level analyses will be reviewed first.

Item-level analyses

While there are numerous item analysis techniques available, only three of the most essential are reviewed here: Item-test correlations (called “point biserial” correlations), item difficulty, and Differential Item Functioning (DIF). Item discrimination indices are also useful for conducting item-level analyses, but are not discussed in this text.

Point biserials

Point biserial calculations result in values between -1.0 and +1.0 that reveal the correlation between the item and the overall test score. Items that have negative values are typically either poor items (with respect to what they are measuring or how they are worded, or both) or are good items that are simply mis-keyed. Values between 0.0 and +0.2 indicate that the item is functioning somewhat effectively, but is not contributing to the overall reliability of the test in a meaningful way. Values of +0.2 and higher indicate that the item is functioning in an effective way, and is contributing to the overall reliability of the test. For this reason, the single best way to increase the reliability of the overall test is to remove items with low (or negative) point biserials.

The point biserial of a test item can be calculated by simply correlating the applicant scores on the test item (coded 0 for incorrect, 1 for correct) to the total scores for each applicant on the overall test used the =PEARSON formula in Microsoft® Excel®. When the total number of items on the test is fewer than 30, a corrected version of this calculation can be done by removing the score of each item from the total score calculation (e.g., when calculating a point biserial for item 1, correlate item 1 to the total score on the test using items 2-30; for item 2, include only items 1 and 3-30 for the total score).

Item difficulty

Item difficulties show the percentage of applicants who answered the item correctly. Items that are excessively difficult or easy (where a very high proportion of test takers are either missing the item or answering it correctly) are typically the items that do not contribute significantly to the overall reliability of the test, and should be considered for removal. Typically, items that provide the highest contribution to the overall reliability of the test are in the mid-range of difficulty (e.g., 40% to 60%).

Differential Item Functioning (DIF)

DIF analyses detect items that are not functioning in similar ways between the focal and reference groups. The Standards (1999), explain that DIF “…occurs when different groups of applicants with similar overall ability, or similar status on an appropriate criterion, have, on average, systematically different responses to a particular item” (p. 13). In some instances, DIF analyses can reveal items that are biased against certain groups (test bias can be defined as any quality of the test item, or the test, that offends or unnecessarily penalizes the applicants on the basis of personal characteristics such as ethnicity, gender, etc.).

It should be noted that there is a very significant difference between simply reviewing the average item score differences between groups (e.g., men and women) and DIF analyses. One might be tempted to just simply evaluate the proportion of men who answered the item correctly (say 80%) versus the proportion of women (say 60%) and then note the size of this differences (20%) when compared relative to other items on the test with less or more spread between groups.

What is wrong with this approach? There is one major flaw: it fails to take group ability levels into account. What if men simply have a 20% higher ability levels than women on the KSAPC measured by the test? Does this make the test, or the items with this level of difference “unfair” or “biased.” Certainly not. In fact, this “simple difference” approach was used in one court case, but received an outcry of disagreement from the professional testing community.

The case was Golden Rule Life Insurance Company v. Mathias (1980) and involved the Educational Testing Service (ETS) and the Illinois Insurance Licensure Examination. In a consent decree related to this case, the parties agreed that test items could be divided into categories (and some items removed) based only on black-white average item score differences on individual items. This practice did not consider or statistically control for the overall ability differences between groups on the test, and was subsequently abandoned after the president of ETS renounced the practice, stating:

. . . the practice was a mistake . . . it has been used to justify legislative proposals that go far beyond the very limited terms of the original agreement . . . We recognized that the settlement compromise was not based on an appropriate ‘bias prevention’ methodology for tests generally. What was to become known as the ‘Golden Rule’ procedure is based on the premise—which ETS did not and does not share—that group differences in performance on test questions primarily are caused by ‘bias.’ The procedure ignores the possibility that differences in performance may validly reflect real differences in knowledge or skill (Anrig, 1987).

The criteria used in the Golden Rule case also sparked dissention in the professional testing community:

The final settlement of the case was based on a comparison of group differences in sheer percentage of persons passing an item, with no effort to equate groups in any measure of the ability the test was designed to assess, nor any consideration of the validity of items for the intended purpose of the test. The decision was clearly in complete violation of the concept of differential item functioning and would be likely to eliminate the very items that were the best predictors of job performance (Anastasi, 1997).

So, it is safe to say that the professional testing community sufficiently rebuked the idea of just simply comparing group differences on items or tests overall. This is precisely where DIF analyses provide a significant contribution to test analyses. Because DIF analyses are different than simple average item score differences between groups and take overall group ability into consideration when detecting potentially bias items, some courts have specifically approved of using DIF analyses for the review and refinement of personnel tests.[iii]

Because DIF analyses function in this way, it is possible that even if 20% of minority group members could answer a particular item correctly and 50% of the whites could answer the item correctly (a large, 30% score gap between the two groups) the item might still escape a “DIF” designation. A DIF designation, however, would occur if the minority group and whites scored very close overall as a group (for example, 55% and 60% respectively), but scored so divergently on the test item.

Consider a 50-item word problem test that measured basic math skills. Assume it was administered to 100 men and 100 women, and men and women scored about equally overall on the test (i.e., their overall averages were about the same). Forty-nine (49) of the 50 items measure math skills using common, every-day situations encountered by men and women alike. One of the items, however, measures math skills using a football example:

You are the quarterback on a football team. It is 4th down with 11 yards to go and you are on your own 41-yard line. You were about to throw a 30-yard pass to a receiver who would have been tackled immediately, but instead you were sacked on the 32-yard line. What is the difference between the yardage that you could have gained (had your pass been caught) versus how much you actually lost?

Does this test item measure some level of basic math? Yes, however, to arrive at the correct answer (39 yards), a test taker needs to use both math skills and football knowledge. Unless football knowledge is related to the job for which this test is being used, this item would possibly show bias (via the DIF analysis) against women.

There are numerous methodologies available for conducting DIF analyses. These methods vary in statistical power (i.e., the ability to detect a DIF item should it exist), calculation complexity, and sample size requirements. Perhaps the most widely used method is known as the Mantel-Haenszel method, which is known as one of the more robust and classical methods for evaluating DIF.[iv]

DIF analyses, because they rely heavily on inferential statistics, are very dependent on sample size. As such, items flagged as DIF based on large sample sizes (e.g., more than 500 applicants) are more reliable than those based on small sample sizes (e.g., less than 100 or so). While the testing literature provides various suggestions and guidelines for sample size requirements for these types of analyses,[v] a good baseline number of test takers for conducting DIF analyses is more than 200 applicants in the reference group (whites or men) and at least 30 in the focal group (i.e., the minority group of interest).

DIF analyses provide the most accurate results on tests that measure the same or highly related KSAPCs (i.e., tests with high reliability). For example, if a 50-item test contains 25 items measuring math skills and 25 items measuring interpersonal abilities and, because these two test areas might not be highly inter-related, the test has low reliability, DIF analyses on such a test would be unreliable and possibly inaccurate. In these circumstances, it would be best to separate the two test areas and conduct separate DIF analyses.

Most DIF analyses output standardized statistical values that can be used to assess varying degrees of DIF (sometimes called Z values). For example, a test item with a Z value of 1.5 would constitute a lesser degree of DIF than a Z value of 3.0, etc.

When should test items be removed based on DIF analyses? There are no firm set of rules for removing items based on DIF analyses, so this practice should be approached with caution. Before removing any item from the test based on DIF analyses, the following considerations should be made:

- The level of DIF: The minimum level of DIF that should be considered “meaningful” is a Z value of 1.645 (such values are statistically significant at the .10 level). Values exceeding 2.58 (significant at the .01 level) are even more substantial. Items that have DIF levels that exceed this value should be more closely scrutinized than items with lower levels of DIF. Items that have only marginal levels of DIF should be carefully evaluated in subsequent test administrations.

- The point biserial of the item: If the item has a very high point biserial (e.g., .30 or higher), but is flagged as DIF, one should be cautious before removing the item. Items with high point biserials contribute to the overall reliability of the test, and if removing the item based on a DIF analysis significantly lowers the reliability of the test, the psychometric quality of the test will be decreased.

- The item-criterion correlation (if available): If the test is based on a criterion-related validity study (where test scores have been statistically related to job performance), evaluate the correlation between the particular item and the measure of job performance. For example, assume a test consisting of 30 items that has an overall correlation to job performance of .30. Then consider that one of these items is flagged as DIF when administered to an applicant pool of several hundred applicants, and this specific item has a 0 (or perhaps even a negative) correlation with job performance when evaluated based on the original validation study. Such an item may be a candidate for removal (when considered along with the other guidelines herein).[vi]

- Qualitative reasons why the item could be flagged as DIF: Items that are sometimes flagged as DIF contain certain words, phrases, or comparisons that require culturally- or group-loaded content or knowledge (which is unrelated to the KSAPC of interest) to provide an adequate response (see the football-based math test item example above). It is sometimes useful to evaluate the item alternative that the DIF group selected over the majority group (e.g., if one group selected option A with high frequency and the other option C).

- The Job Expert validation ratings for the item: Is the specific aspect of the KSAPC measured by the item (not just the general KSAPC to which the item is linked) necessary for the job? Did this item receive clear, positive validation ratings from the Job Expert panel? If the item had an unusual number of red flags when compared to the other items that were included on the test, it may be a candidate for removal.

- The DIF values “for” or “against” other groups: If an item shows high levels of DIF against one group, but “reverse DIF” for another group, caution should be used before removing the item. However, if the group showing the high levels of DIF is based on a much larger sample size than the group with reverse DIF, a greater weight should be given to the group with the larger sample size.

- How groups scored on the subscales of the test: DIF analyses assume that the test is measuring a single attribute or dimension (or multiple dimensions that are highly correlated). However, sometimes groups score differently on various subscales on a test, and these differences can be the reason that items are flagged DIF (i.e., rather than the item itself being DIF against the group, it may only be flagged as DIF because it is part of a subscale on which subgroups significantly differ). For example, consider a test with the following characteristics: high overall internal consistency (reliability of .90), and two subscales: Scale A and Scale B. Assume that the average score for men is 65% on Scale A, 75% on Scale B, and 70% overall. The average score for Women is score 70% overall, but they have opposite scale scores compared to men (75% on Scale A and 65% on Scale B). Then assume that a DIF analysis with all items included showed that one item on Scale B was DIF against women. In this case, it would be useful to remove all items from Scale A and re-run the DIF analysis with only Scale B items included to determine if the item was still DIF against women. This process effectively controls for the advantage that women had on the overall test because of their higher score on Scale A.

Test-level analyses

There are essentially two types of overall, test-level analyses: descriptive and psychometric. Descriptive analyses pertain to the overall statistical characteristics of the test, such as the average (mean), dispersion of scores (standard deviation), and others. The psychometric analyses evaluate whether the test is working effectively (e.g., test reliability). Each of these is discussed below.

Descriptive test analyses

The two primary descriptive types of test analyses are the mean (mathematical average) and standard deviation (average dispersion—or spread—of the test scores around the mean). Only a very brief mention of these two concepts will be provided here.

The test mean shows the average score level of the applicants who took the test. Note that this does not have any bearing whatsoever on whether the applicant pool is qualified (at least the mean by itself does not). While the mean can be a useful statistic for evaluating the overall test results, it should be given less consideration when evaluating mastery-based or certification/licensing tests (because certain score levels are needed for passing the test, irrespective of the fluctuation in score averages based on various applicant groups).

The standard deviation of the test is a statistical unit showing the average score dispersion of the overall test scores, is also useful for understanding the characteristics of the applicant pool. Typically, 68% of applicant scores will be contained within one standard deviation above and below the test mean, 95% will be contained within two, and 99% within three. The standard deviation can be used to evaluate whether the applicants, as a whole, are scoring too high or low on the test (hence the test is losing out on valuable information about test takers because they are magnetized to one extreme of the distribution).

The mean and standard deviation are sometimes inappropriately used for setting cutoff scores.[vii]Test developers are encouraged to use these two statistics for mostly informative, rather than instructive, purposes.

Psychometric analyses

Like item-level analyses, numerous analyses can be done to evaluate the quality of the overall test. This discussion will be limited to the most frequently used, essential analyses for written tests, which include common forms of test reliability and the Standard Error of Measurement (SEM). Two other advanced psychometric concepts that pertain mostly to mastery-based tests (tests used with a pass/fail cutoff based on a pre-set level of proficiency required for the job) will also be discussed at the end of this section: Decision Consistency Reliability (DCR) and Kappa Coefficients.

Test reliability

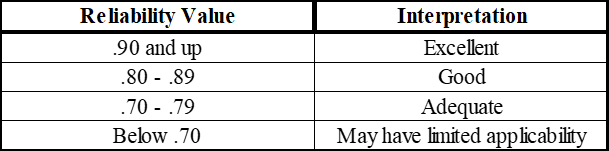

Test reliability pertains to the consistency of applicant scores. A highly reliable test is one that measures a one-dimensional or inter-related KSAPC in a consistent way. There are several factors that can have a significant impact on the reliability of a written test, however, the most important factor is whether the items on the test “hang together” statistically. The items on a test need to be highly inter-correlated for a test to have high overall reliability. The Uniform Guidelines and professional standards provide no minimum thresholds for what constitutes acceptable levels of reliability. The US Department of Labor (2000, p. 3-3), has provided some general guidelines.

Table 3‑2 Guidelines for Interpreting Test Reliability

Perhaps the most common type of reliability analysis used for written tests is Cronbach’s Alpha. This method is widely used by statistical and psychometric software because it provides a highly accurate measure regarding the consistency of applicant scores. The Kuder-Richardson 20 (KR-20) formula is very similar to the Cronbach’s Alpha, but can be used for dichotomously-scored items only (i.e., items that have only two possible outcomes: correct or incorrect). Cronbach’s Alpha, however, can be used for polytomous items (i.e., items that have more than one point value).

The Kuder-Richardson 21 (KR-21) formula is another method for evaluating the overall consistency of the test. It is typically more conservative than Cronbach’s Alpha, and is calculated by considering only each applicant’s total score (whereas the Cronbach’s Alpha method takes item-level data into consideration).

Standard Errors of Measurement (SEMs)

To a certain extent, test reliability exists so that the Standard Error of Measurement (SEM) can be calculated. The two go hand-in-hand. The (traditional) SEM can be easily calculated by multiplying the Standard Deviation of the test by the square root of one minus the reliability of the test. This can be calculated in Microsoft® Excel® as: =SD*(SQRT(1-Reliability)), where SD is the standard deviation of applicant overall test scores and Reliability is the test reliability (using Cronbach’s Alpha, KR-20, or the KR-21 formula, etc.).

The SEM provides a confidence interval of an applicant’s “true score” around their “obtained score.” An applicant’s true score represents their true, actual ability level on the overall test, whereas an applicant’s obtained score represents the score that they “just happened to obtain on the day the test was given.” SEMs help testing professionals understand that if the applicant as much as sneezes during a hypothetical second test administration of an equally difficult test, their score could be lower than obtained on the first administration. Likewise, if the applicant had a better night’s sleep for the second administration, their score would possibly be higher than the first administration.

How this concept translates into testing is relatively straight-forward. After the SEM has been calculated, it can be used to install boundaries for where each applicant’s true abilities lie on the test. Assume the SEM for a written test is 3.0. This means that an applicant who scores 50 on the test most likely (with 68% confidence) has a “true score” on the test ranging between 47 and 53 (1 SEM, or 3.0 points, above and below their obtained score). Using 2 SEMs (or 6 points above and below their obtained score) provides a 95% likelihood of including a score that represents their true ability level. Using 3 SEMs provides 99% confidence.

There is one small limitation with the traditional SEM discussed above (the one calculated using the formula above). This limitation is due to the fact that a test’s reliability typically changes throughout the distribution. In other words, the reliability of the highest scorers on the test is sometimes different than the average, and from the lowest scorers. This is where the Conditional SEM comes in.

Conditional Standard Error of Measurement

The Standards (1999) require the consideration of the Conditional Standard Error of Measurement when setting cutoff scores (as opposed to the traditional Standard Error of Measurement) (see pages 27, 29, 30 and Standard 2.2, 2.14, and 2.15 of the Standards).

The traditional SEM represents the standard deviation of an applicant’s true score (the score that represents the applicant’s actual ability level) around his or her obtained (or actual) score. The traditional SEM considers the entire range of test scores when calculated. Because the traditional SEM considers the entire range of scores, its accuracy and relevance is limited when evaluating the reliability and consistency of test scores within a certain range of the score distribution.

Most test score distributions have scores bunched in the middle and spread out through the low and high range of the distribution. Those applicants who score in the lowest range of the distribution lower the overall test reliability (hence affecting the size of the SEM) by adding chance variance caused by guessing and not by possessing levels of the measured KSAPC that are high enough to contribute to the true score variance of the test. High scorers can also lower the overall reliability (and similarly affect the size of the SEM) because high-scoring applicants possess exceedingly high levels of the KSAPC being measured, which can also reduce the true variance included in the test score range. Figure 3-1 shows how the SEM is not constant throughout a score distribution (this chart is derived from data provided in Lord, 1984).

Figure 3‑1 Standard Error of Measurement (SEM) by Score Level

Because the SEM considers the average reliability of scores throughout the entire range of scores, it is less precise when considering the scores of a particular section of the score distribution. When tests are used for human resource decisions, the entire score range is almost never the central concern. Typically in human resource settings, only a certain range of scores are considered (i.e., those scores at or near the cutoff score, or the scores that will be included in a banding or ranking procedure).

The Conditional SEM attempts to avoid the limitations of the SEM by considering only the score range of interest when calculating its value. By only considering the scores around the critical score value, the Conditional SEM is the most accurate estimate of the reliability dynamics of the test that exist around the critical score.

Several methods are available for calculating the Conditional SEM. The Thorndike (1951) method [viii] is a recommended procedure because it can be readily calculated using spreadsheet programs and because it provides results comparable to more sophisticated methods.[ix] It is further recommended because the procedure considers true score and error variance throughout the entire score distribution, which allows its application on tests that measure different KSAPCs.

While the procedure may be conducted with less than 30 applicants, it is likely that the results may be more stable if 30 or more applicants are included (Feldt et al. 1985, p. 354) The test may have any number of items, but more meaningful results will be obtained with tests with 10 or more items (Kolen, Hanson, & Brennan, 1992, p. 293). The Thorndike method can be calculated by following these steps:

- Select a group of test scores within a close range of the cutoff score (remaining as close as possible to the cutoff score value and only widening to gather an acceptable sample size of 30 or more applicants [x]).

- For each applicant selected, divide their test score into two sections: one representing their score for all odd items on the test and one for all even items. If there is not an equal number of items for each of these sections (the odd score and even score), remove one item from the section with the extra item (e.g., the last item on the test).

- Calculate a “difference” score for each applicant by subtracting the two test scores (total odd score minus even score).

- Calculate the standard deviation of the difference scores. The resulting value is the Conditional SEM, or the standard error of measurement that is related to the set of scores within close range of the critical (or “minimum qualification” score).

Practitioners will observe that the Conditional SEM typically varies throughout the distribution as it accurately reflects the changing levels of reliability and variance throughout the score range.

Psychometric analyses for mastery-based tests

Test that require pre-determined levels of proficiency that are based on some job-related requirements are mastery-based tests. Mastery-based tests are used to classify applicants as “masters” or “non-masters,” or those who “have enough competency” or “do not have enough competency” with respect to the KSAPCs being measured by the test (see relevant section in BCGi Resources) and Standard 14.15 of the Standards, 1999). Two helpful statistics for mastery-based tests are Decision Consistency reliability (DCR) and Kappa Coefficients.

Decision Consistency Reliability (DCR)

DCR is perhaps the most important type of reliability to consider when interpreting reliability and cutoff score effectiveness for mastery-based tests. DCR attempts to answer the following question regarding a mastery-level cutoff on a test: If the test was hypothetically administered to the same group of applicants a second time, how consistently would the test pass the applicants (i.e., classify them as “masters”) who passed the first administration again on a second administration? Similarly, DCR attempts to answer: “How consistently would applicants who were classified by the test in the first administration as ‘non-masters’ fail the test the second time?” This type of reliability is different than internal consistency reliability (e.g., Cronbach’s Alpha, KR-21), which considers the consistency of the test internally, without respect to the consistency with which the cutoff classifies applicants as masters and non-masters.

One very important characteristic about DCR reliability is that it is inherently different than the other forms of reliability discussed above (i.e., Cronbach’s Alpha, KR-20, KR-21). Because DCR pertains to the consistency of classification of the test, which is an action of the test (rather than an internal characteristic of the test which is what the other reliability types reveal), its value cannot be used in the classical SEM formula.

Calculating DCR is beyond the built-in commands available in most spreadsheet programs, but can be calculated using the methods described in Subkoviak (1988) and Peng & Subkoviak (1980) (the TVAPÒ Software in the Evaluation CD includes these calculations built into Microsoft® Excel® using calculations and embedded programming). DCR values between .75 and .84 can be considered “limited”; values between .85 and .90 considered “good”; and values higher than .90 considered “excellent” (Subkoviak, 1988).

Kappa Coefficients

A Kappa Coefficient explains how consistently the test classifies “masters” and “non-masters” beyond what could be expected by chance. This is essentially a measure of utility for the test. Calculating Kappa Coefficients also requires advanced statistical software or programming. For mastery-based tests, Kappa Coefficients exceeding .31 indicate adequate levels of effectiveness, and levels of .42 and higher are good (Subkoviak, 1988).

[ii] Classical test analysis refers to the test analysis techniques that use conventional analysis concepts and methods. More modern test theories exist (e.g., Item Response Theory), but are not discussed in this text.

[iii] See, for example: Edwards v. City of Houston, 78 F.3d 983, 995 (5th Cir., 1996) and Houston Chapter of the International Association of Black Professional Firefighters v. City of Houston, No. H 86 3553, U.S. Dist. Ct. S.D. Texas (May 3, 1991).

[iv] Narayanan, P, & Swaminathan, H. (1995). Performance of the Mantel-Haenszel and simultaneous item bias procedures for detecting differential item functioning. Applied Psychological Measurement, 18, 315-328.

[v] See: Mazor, K. M., Clauser, B. E., & Hambleton, R. K. (1992), The effect of sample size on the functioning of the Mantel-Haenszel statistic. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 52, 443-451; Narayanan, P. & Swaminathan, H. (1995), Performance of the Mantel-Haenszel and simultaneous item bias procedures for detecting differential item functioning. Applied Psychological Measurement, 18, 315-328; and Swaminathan, H. & Rogers, H. J. (1990), Detecting differential item functioning using logistic regression procedures. Journal of Educational Measurement, 27, 361-370.

[vi] In any given criterion-related validity study, it is not likely that all items on the test will be statistically related to job performance (this is not the requirement for tests based on criterion-related validity, but rather that only the overall test is sufficiently correlated). However, if there is no specific evidence that the test item is related to job performance, while simultaneously there is specific evidence that the item could possibly be unfair against a certain group, it is justifiable to consider the item for removal (the other factors listed should also be considered).

[vii] See for example Evans v. City of Evanston (881 F.2d 382, 7th Cir., 1989).

[viii] Thorndike, R. L. (1951). Reliability. In E. F. Lindquist (Ed.). Educational measurement (pp. 560-620). Washington DC: American Council on Education.

[ix] The Qualls-Payne (1992) study showed that the average Conditional SEM produced by the Thorndike method (across 13 different score levels) produced CSEM values that were very close to five other methods (the average Conditional SEM value produced by the Thorndike method was 2.57, while the other five methods produced values of 2.81, 2.60, 2.58, 2.55, and 2.58). Further, a study conducted by Feldt (Feldt, L. S., Steffen, M., & Gupta, N. C. (1985, December), ‘A comparison of five methods for estimating the standard error of measurement at specific score levels’, Applied Psychological Measurement, 9 (4), 351-361) shows that, while the Thorndike method is less complicated than some other methods (i.e., those based on ANOVA, IRT, or binomial methods), it is “integrally related” and generally produces very similar results.

[x] Fredrick Lord suggests selecting the scores of applicants “at (or near) a given observed score” (1984, p. 240); Feldt et al. (1985, p. 352) suggests grouping applicants into “short intervals of total score”; Feldt also suggested a procedure to “break the entire applicant sample into subgroups according to total score, using intervals of 3 or 5 points for the sub grouping” (personal communication, April 7, 2000), which allows the calculation of the Conditional SEM for each interval, with each Conditional SEM being a direct estimate of the CSEM for the total score equal to the mid-point of the interval; R. K. Hambleton suggests including scores “within a point or two of the passing score” (personal communication, May 23, 2000).

Seven Steps for Developing a Content Valid Job Knowledge Written Test

Job knowledge can be defined as, “…the cumulation of facts, principles, concepts and other pieces of information that are considered important in the performance of one’s job” (Dye, Reck, & McDaniel, 1993, p. 153).[i] As applied to written tests in the personnel setting, knowledge can be categorized as: declarative knowledge—knowledge of technical information; or procedural knowledge—knowledge of the processes and judgmental criteria required to perform correctly and efficiently on the job (Hunter, 1983; Dye et al., 1993).[ii]

While job knowledge is not typically critical for many entry-level positions, it clearly has its place in many supervisory positions where having a command of certain knowledge areas is essential for job performance. For example, if a Fire Captain, responsible for instructing firefighters who have been deployed to extinguish a house fire, does not possess a mastery-level of knowledge required for the task, the safety of the firefighters and the public could be in jeopardy. It is not feasible to require a Fire Captain in this position to refer to textbooks and determine the best course of action, but rather he or she must have the particular knowledge memorized.

As relevant sections in BCGi Resources describes, there are a variety of steps that should be followed to ensure that a job knowledge written test is developed and utilized properly. Depending upon the size and type of the employer, they may be faced with litigation from the EEOC, the DOJ, the OFCCP (under DOL), or a private plaintiff attorney. Each year, employers accused of utilizing tests that have adverse impact spend millions of dollars defending litigated promotional processes.[iii]

An unlawful employment practice based on adverse impact may be established by an employee under the 1991 Civil Rights Act only if:

- A(i) a complaining party demonstrates that a respondent uses a particular employment practice that causes a disparate impact on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, and

- The respondent fails to demonstrate that the challenged practice is job-related for the position in question and consistent with business necessity; or,

- A(ii) the complaining party makes the demonstration described in subparagraph (C) with respect to an alternate employment practice, and the respondent refuses to adopt such alternative employment practice (Section 2000e-2[k][1][A][i])

In litigation settings, addressing these standards is typically conducted by completing a validation study (using any of the acceptable types of validity). This Appendix is designed to provide seven steps for developing a job-related and court-defensible process for creating a content valid job knowledge written test used for hiring or promoting employees.

The seven steps below are designed to address the essential requirements based on the Uniform Guidelines (1978), the Principles (2003), and the Standards (1999) [iv]4:

- Conduct a job analysis;

- Develop a selection plan;

- Identify test plan goals;

- Develop the test content;

- Validate the test;

- Compile the test;

- Conduct post-administration analyses.

Step 1: Conduct a job analysis

The foundational requirement for developing a content valid job knowledge written test is a current and thorough job analysis for the target position. Brief 1-2 page “job descriptions” are almost never sufficient for showing validation under the Uniform Guidelines unless, at a bare minimum, they include:

- Job Expert input and/or review;

- Job duties and KSAPCs that are essential for the job;

- Operationally defined KSAPCs.

In practice, we find that where validity is required, updated job analyses typically need to be developed. Ideally, creating a Uniform Guidelines-style job analysis would include the following ratings for job duties (see relevant sections of BCGi Resources for a complete discussion on completing job analyses).

Frequency (Uniform Guidelines, Section 15B3; 14D4)[v]

This duty is performed (Select one option from below) by me or other active (target position) in my department.

- annually or less often

- semi-annually (approx. 2 times/year)

- quarterly (approx. 4 times/year)

- monthly (approx. 1 time/month)

- bi-weekly (approx. every 2 weeks)

- weekly (approx. 1 time/week)

- semi-weekly (approx. 2 to 6 times/week)

- daily/infrequently (approx. 1 to 6 times/day)

- daily/frequently (approx. 7 or more times/day)

Importance (Uniform Guidelines, Section 14C1, 2, 4; 14D2, 3; 15C3, 4, 5; 15D3)

Competent performance of this duty is (Select one option from below) for the job of (target position) in my department.

- not important: Minor significance to the performance of the job.

- of some importance: Somewhat useful and/or meaningful to the performance of the job.

- Improper performance may result in slight negative consequences

- important: Useful and/or meaningful to the performance of the job.

- Improper performance may result in moderate negative consequences

- critical: Necessary for the performance of the job.

- Improper performance may result in serious negative consequences

- very critical: Necessary for the performance of the job, and with more extreme

- Improper performance may result in very serious negative consequences

Ideally, creating a Uniform Guidelines-style job analysis requires that each KSAPC has the following ratings:

Frequency (Uniform Guidelines, Section 15B3; 14D4) 16

This KSAPC is performed (Select one option from below) by me or other active (target position) in my department.

- annually or less often

- semi-annually (approx. 2 times/year)

- quarterly (approx. 4 times/year)

- monthly (approx. 1 time/month)

- bi-weekly (approx. every 2 weeks)

- weekly (approx. 1 time/week)

- semi-weekly (approx. 2 to 6 times/week)

- daily/infrequently (approx. 1 to 6 times/day)

- daily/frequently (approx. 7 or more times/day)

Importance (Uniform Guidelines, Section 14C1, 2, 4; 14D2, 3; 15C3, 4, 5; 15D3)

This KSAPC is (Select one option from below) for the job of (target position) in my department.

- not important: Minor significance to the performance of the job.

- of some importance: Somewhat useful and/or meaningful to the performance of the job.

- Not possessing adequate levels of this KSAPC may result in slight negative consequences

- important: Useful and/or meaningful to the performance of the job.

- Not possessing adequate levels of this KSAPC may result in moderate negative consequences

- critical: Necessary for the performance of the job.

- Not possessing adequate levels of this KSAPC may result in serious negative consequences

- very critical: Necessary for the performance of the job, and with more extreme consequences

- Not possessing adequate levels of this KSAPC may result in very serious negative consequences

Differentiating “Best Worker” Ratings (Uniform Guidelines, Section 14C9)

Possessing above-minimum levels of this KSAPC makes (Select one option from below) difference in overall job performance.

- No

- Little

- Some

- A significant

- A very significant

Note: Obtaining ratings on the “Best Worker” scale is not necessary if the job knowledge written test will be used only on a pass/fail basis (rather than ranking final test results).

When Needed (Uniform Guidelines, Section 5F; 14C1)

Possessing (Select one option from below) of this KSAPC is needed upon entry to the job for the (target position) position in your department.

- None or very little

- Some (less than half)

- Most (more than half)

- All or almost all

In addition to these four KSPAC rating scales, we recommend that a mastery level scale be used when validating written job knowledge tests. The data from these ratings are useful for choosing the job knowledges that should be included in a written job knowledge test, and are useful for addressing Section 14C4 of the Uniform Guidelines, which require that job knowledges measured on a test be “. . . operationally defined as that body of learned information which is used in and is a necessary prerequisite for observable aspects of work behavior of the job.” We suggest using an average rating threshold of 3.0 on the mastery-level scale for selecting job knowledges to be included on job knowledge tests. A sample mastery level scale is listed below:

Mastery Level (Uniform Guidelines, Section 14C4)

A (Select one option from below) level of this job knowledge is necessary for successful job performance.

1—Low: none or only a few general concepts or specifics available in memory in none or only a few circumstances without referencing materials or asking questions.

2—Familiarity: have some general concepts and some specifics available in memory in some circumstances without referencing materials or asking questions.

3—Working knowledge: have most general concepts and most specifics available in memory in most circumstances without referencing materials or asking questions.

4—Mastery: have almost all general concepts and almost all specifics available in

memory in almost all circumstances without referencing materials or asking questions.

Finally, a duty/KSAPC linkage scale should be used to ensure that the KSAPCs are necessary to the performance of important job duties. A sample duty/KSAPC linkage scale is provided below:

Duty/KSAPC Linkages (Uniform Guidelines, Section 14C4)

This KSAPC is ________ to the performance of this duty.

- Not important

- Of minor importance

- Important

- Of major importance

- Critically important

When Job Experts identify KSAPCs necessary for the job, it is helpful if they are written in a way that maximizes the likelihood of job duty linkages. When KSAPCs fail to provide enough content to link to job duties, their inclusion in a job analysis is limited. Listed below are examples of a poorly written and a well written KSAPC from a firefighter job analysis:

Example of a poorly written KSAPC:

Knowledge of ventilation practices.

Example of a well written KSAPC:

Knowledge of ventilation practices and techniques to release contained heat, smoke, and gases in order to enter a building. Includes application of appropriate fire suppression techniques and equipment (including manual and power tools and ventilation fans).

Step 2: Develop A Selection Plan

The first step in developing a selection plan is to review the KSAPCs from the job analysis and design a plan for measuring the essential KSAPCs using various selection procedures (particularly, knowledge areas). Refer to the Selection Plan section in BCGi Resources for specific criteria for selecting KSAPCs for the selection process. At a minimum, the knowledge areas selected for the test should be important, necessary on the first day of the job, required at some level of mastery (rather than easily looked up without hindrance on the job), and appropriately measured using a written test format. Job knowledges that meet these criteria are selected for inclusion in the “Test Plan” below.

Step 3: Identify Test Plan Goals

Once the KSAPCs which will be measured on the test have been identified, the test sources relevant for the knowledges should be identified. Review relevant job-related materials and discuss the target job in considerable detail with Job Experts. This will focus attention on job specific information for the job under analysis. Review the knowledges that meet the necessary criteria and determine which sources and/or textbooks are best suited to measure the various knowledges. It is imperative that the selected sources do not contradict one another in content.

Once the test sources have been identified, determine whether or not preparatory materials will be offered to the applicants. If preparatory materials are used, ensure that the materials are current, specific, and released to all applicants taking the test. In addition to preparatory materials, determine if preparatory sessions will be offered to the applicants.

Use of preparatory sessions appear to be beneficial to both minority and non-minority applicants, although they do not consistently reduce adverse impact (Sackett, Schmitt, Ellingson, & Kabin, 2001).[vi] If study sessions are conducted, make every attempt to schedule study sessions at a location that is geographically convenient to all applicants and is offered at a reasonable time of day. Invite all applicants to attend and provide plenty of notice of the date and time.

Following the identification of the knowledge areas and source materials that will be used to develop the job knowledge written test, identify the number of test items that will be included on the test. Be sure to include enough items to ensure high test reliability. Typically, job knowledge tests that are made up of similar job knowledge domains will generate reliability levels in the high .80s to the low .90s when they include 80 items or more.

Consider using Job Expert input to determine internal weights for the written test. Provide Job Experts with the list of knowledges to be measured and ask experts to distribute 100 points among the knowledges to obtain a balanced written test. See Table 3-3 for a sample of a knowledge weighting survey used to develop a written test used for certifying firefighters (this type of test would be used by fire departments that hire only pre-trained firefighters into entry-level positions).

Table 3‑3 Firefighter Certification Test Development Survey

Attempt to obtain adequate sampling of the various knowledges and ensure that there are a sufficient number of items developed to effectively measure each knowledge at the desired level. Note that some knowledges will require more items than others for making a “sufficiently deep” assessment. The test should be internally weighted in a way that ensures a sufficient measurement of the relevant knowledge areas.

Following the determination of the length of the test and the number of items to be derived from each source, determine the types of items that will be included on the test. One helpful tool is a process-by-content matrix to ensure adequate sampling of job knowledge content areas and problem-solving processes. Problem-solving levels include:

- Knowledge of terminology

- Understanding of principles

- Application of knowledge to new situations

While knowledge of terminology is important, the understanding and application of principles may be considered of primary importance. The job knowledge written test should include test items that ensure the applicants can define important terms related to the job and apply their knowledge to answer more complex questions. Job Experts should consider how the knowledge is applied on the job (e.g., factual recall, application, etc.) when determining the types of items to be included on the final test form (see Table 3-4 for a sample process-by-content matrix for a police sergeant written test).

Table 3‑4 Process -by-Content Matrix: Police Sergeant

Step 4: Develop The Test Content

After the number and types of test items to be developed has been determined, select a diverse panel of four to ten Job Experts (who have a minimum of one year experience) to review the test plan to ensure compliance with the parameters. Have each Job Expert sign a “Confidentiality Form.” If the Job Experts are going to write the test items, provide item-writing training (see Attachment C in the TVAP® User Manual on the Evaluation CD for item-writing guidelines) and have Job Experts peer review the items.

Once the Job Experts have written the items to be included in the test bank, ensure proper grammar, style, and consistency. Additionally, make certain that the test plan requirements are met. Ensure that the items address the criteria on the TVAP Survey (see the Evaluation CD for the TVAP Software and corresponding survey for rating/validating test items). Assume that 20-30% of the test items will not meet the requirements of the TVAP Survey and account for this attrition by developing a surplus of test items. Once the bank of test items has been created, provide the final test version to the panel of Job Experts for the validation process (the next step).

Step 5: Validate The Test

Use the TVAP Survey to have Job Experts assign various ratings to the items in the test bank. Additionally, have the Job Experts identify an appropriate time limit. A common rule-of-thumb used by practitioners to determine a written test cutoff time is to allow one minute per test item plus thirty additional minutes (e.g., a 150-item test would yield a three hour time limit).[vii] A reasonable time limit would allow for at least 95% of the applicants to complete the test within the time limit.

Step 6: Compile The Test

Evaluate the Job Expert ratings on the TVAP Survey and discard those items that do not meet the criteria (see TVAP User Manual). Once the Job Experts have assigned the various ratings to each of the test items, analyze the “Angoff” ratings identified by Job Experts. Discard raters whose ratings are statistically different from other raters by evaluating rater reliability and high/low rater bias. Calculate the difficulty level of the test (called the pre-administration cutoff percentage).

Step 7: Post-Administration Analyses

Following the administration of the job knowledge written test, conduct an item-level analysis of the test results to evaluate the item-level qualities (such as the point-biserial, difficulty level, and Differential Item Functioning [DIF] of each item). Use the guidelines in BCGi Resources for deciding which items to keep or remove for this administration (or improve for later administrations). In addition to the guidelines proposed in BCGi Resources for evaluating when to discard an item due to DIF, consider the following excerpt from Hearn v. City of Jackson (Aug. 7, 2003)14 where DIF was being considered for a job knowledge test:

Plaintiffs suggest in their post-trial memorandum that the test is subject to challenge on the basis that they failed to perform a DIF analysis to determine whether, and if so on which items, blacks performed more poorly than whites, so that an effort could have been made to reduce adverse impact by eliminating those items on which blacks performed more poorly. . . Dr. Landy testified that the consensus of professional opinion is that DIF modifications of tests is not a good idea because it reduces the validity of the examination. . . Dr. Landy explained: “The problem with [DIF] is suppose one of those items is a knowledge item and has to do with an issue like Miranda or an issue in the preservation of evidence or a hostage situation. You’re going to take that item out only because whites answer it more correctly than blacks do, in spite of the fact that you’d really want a sergeant to know this [issue] because the sergeant is going to supervise. A police officer is going to count on that officer to tell him or her what to do. So you’re reducing the validity of the exam just for the sake of making sure that there are no items in which whites and blacks do differentially, or DIF, and he’s assuming that the reason that 65 percent of the blacks got it right and 70 percent of the whites got it right was that it’s an unfair item rather than, hey, maybe two or three whites or two or three blacks studied more or less that section of general orders.”

Certainly this excerpt provides some good arguments against discarding items based only on DIF analyses. These issues and the guidelines discussed in relevant sections of BCGi Resources should be carefully considered before removing items from a test.

After conducting the item-level analysis and removing items that do not comply with acceptable ranges, conduct a test-level analysis to assess descriptive and psychometric statistics (e.g., reliability, standard deviation, etc.). Adjust the unmodified Angoff by using the Standard Error of Measurement or the Conditional Standard Error of Measurement where applicable (see relevant sections of BCGi Resources for a complete discussion on this subject).

In summary, developing a content valid job knowledge written test for hiring/promoting employees (where the job requires testing for critical job knowledge areas!) is the safest route to avoid potential litigation. If the test has adverse impact, validate. Pay particular attention in addressing the Uniform Guidelines, Principles, and Standards (in that order, based on the weight they are typically given in court), and remember that a house is only as strong as its foundation. Be sure to base everything on a solid job analysis.

Steps for Developing a Customized Personality Test Using a Concurrent Criterion-related Validity Strategy

This article provides “hands on” steps for developing and validating a low-adverse impact personality assessment for organizations that have at least 250 job incumbents in a specific job title or job group.

One of the most important human performance factors is personality. We’ve all known co-workers who stumble in job performance areas because of lack of drive, initiative, focus, determination, conscientiousness, or other characteristics that are separate and distinct from “smarts.” Workers who are lacking in some of these factors will often fall short in a variety of job performance areas, including maintaining productive professional relationships, effectively solving interpersonal conflict issues that arise with other co-workers or clients, staying focused on completing projects, or completing quality work.

How can HR professionals capture these “soft” factors in the hiring and selection process? Sometimes conducting in-depth interview will provide insight into these areas. Evaluating work history and patterns can also give insight into these elusive traits. But these investigations take time—precious time that HR professionals sometimes don’t have. Further, HR professionals in mid- to large-sized organizations need to screen hundreds and sometimes thousands of job candidates, making such in-depth investigations less than feasible. This is where written personality assessments play an integral role in the hiring process. Many personality measures are brief, to-the-point, and effective. But which traits are needed for the jobs in your organization? How can a valid personality test be developed for your organization? These questions and others will be answered in this brief “how to” guide for developing validated personality tests.

Before unpacking the development recipe, however, two issues should be stated. First, personality measures are a great way to lower adverse impact in most hiring processes. Because personality tests typically have less than half of the adverse impact[viii] commonly generated by cognitive ability tests, they are in fact one of several effective ways to reduce adverse impact in your organization’s hiring process. However, cognitive ability tests are oftentimes solid predictors of job success, and should not be removed from a hiring process for the sole reason of lowering adverse impact. The ideal selection process is one that proportionately measures most of the key qualification factors needed for success—with cognitive ability and personality factors being just two such components. Second, personality tests come by a dozen different names. Sometimes they are called “work style” tests; sometimes they are referred to as “profiles”; and sometimes just “personality measures.” In this article, we are focusing on true, inherent personality factors, rather than attitudes and values that are sometimes more changeable over time.